Unforgotten

Explore some of the stories of the Mt. Zion and Female Union Band Society Cemeteries through 3D captures

...death reflects life, and the treatment of Black people in life is reflective of treatment of Black people in death.

- Lisa Fager, 2024

About the Cemeteries

The Mt. Zion and Female Union Band Society Cemeteries are the oldest majority Black cemeteries known to exist in the District of Columbia. The Mt Zion Cemetery was established by the Montgomery Street Methodist Church (later the Dumbarton Street Methodist Church) in 1808 as the Old Methodist Burying Ground, while the Female Union Band Society Cemetery was founded separately in 1842 by a benevolent organization of free Black women. They sit adjacent to each other, nestled into a quiet corner of the Georgetown neighborhood and Rock Creek Park. Together, they reflect the efforts of Black communities to care for one another through mutual aid and long lasting relationships.

These cemeteries hold the remains of thousands of people, many of whom may never be known to us. The stories below, of the individuals and places that inhabit these grounds, offer only a small glimpse into the rich tapestry of Black Georgetown and Washington D.C. life that each person interred here helped shape at some point in their lives. Many of the people laid to rest here escaped the horrors of race-based chattel slavery before finding themselves a part of this community.

As you browse this exhibit, I ask that you try to remember one name or story and share it with someone else at some point in the future. Many of these histories survived through oral tradition. Consider honoring that legacy by carrying their memory forward.

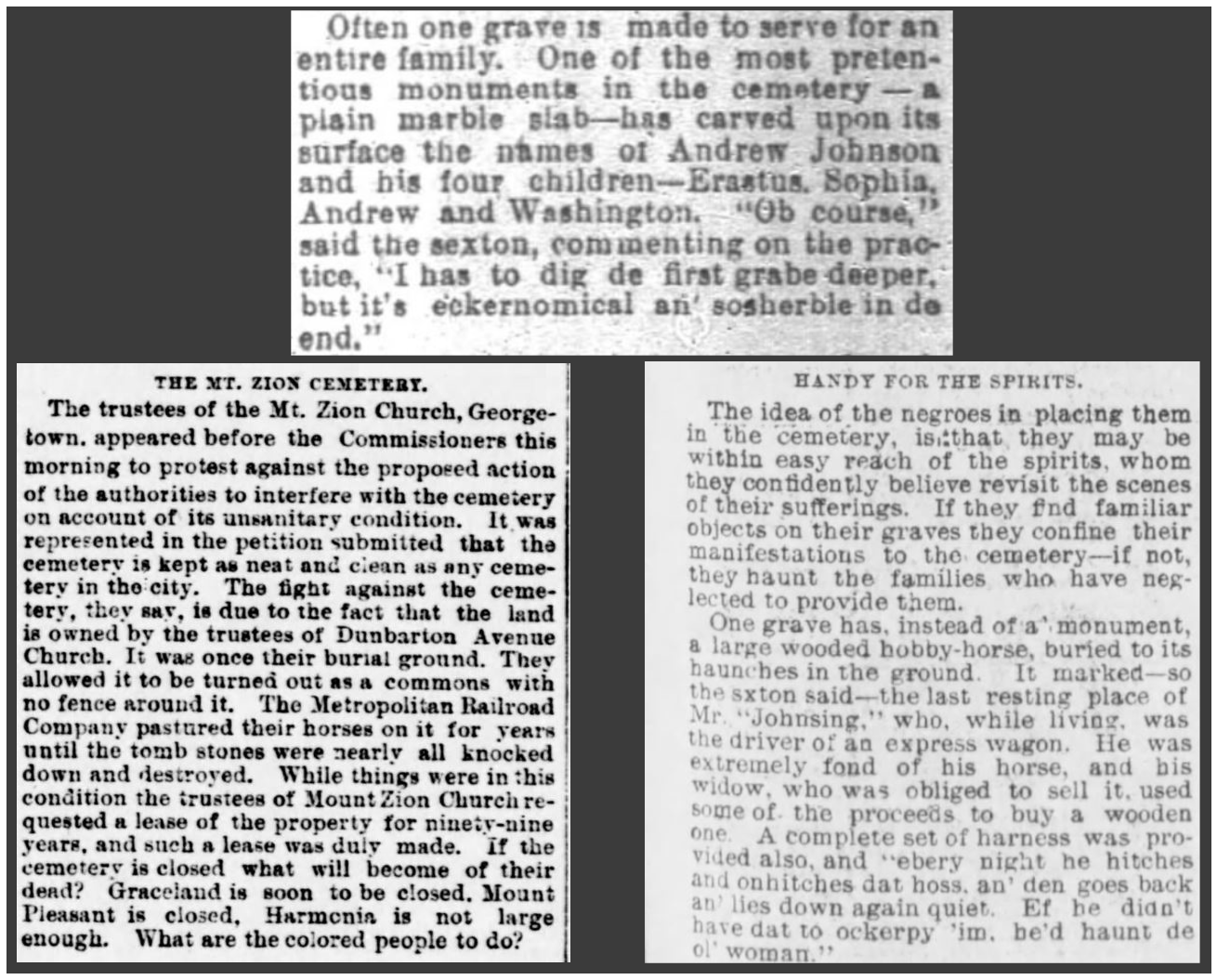

The Historical Perception of Black Cemeteries

Snippets of articles published and repurposed from newspapers across America in the 20th century, depicting the mainstream perception of Black people and their cemeteries. The othering of African-American memorialization practices (which can be traced back to pre-colonial Africa), the use of eye dialect to depict the accent of a Black sexton, and the perception of a maintained Black cemetery as "unsanitary" reveals an intent to demean, exoticize, and render as spectacle the traditions and labor of Black communities. | Source: Black Georgetown Foundation

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, Black cemeteries were frequently misrepresented by observers outside of their community as unsanitary, superstitious, or unserious, despite being sites of deep cultural memory. These perceptions, like those found in the news articles above, would seek to other them and describe them as spectacles. Memorial practices like placing toys or objects on a grave are rooted in many of the cultures that were enslaved and forcibly moved to the Americas through the transatlantic slave trade, although they were often framed as primitive. Even in cases where Black cemeteries were maintained, like Mount Zion, officials and press still depicted them as unhygienic or disordered while ignoring the structural neglect forced upon them from structural institutions (in this case, a railroad company using Mount Zion to store horses).

These dismissals of the dignity of Black death rituals would help shape public perception on them for generations. Understanding and challenging these narratives is essential to understanding their true cultural and historical significance.

About the Gravestones

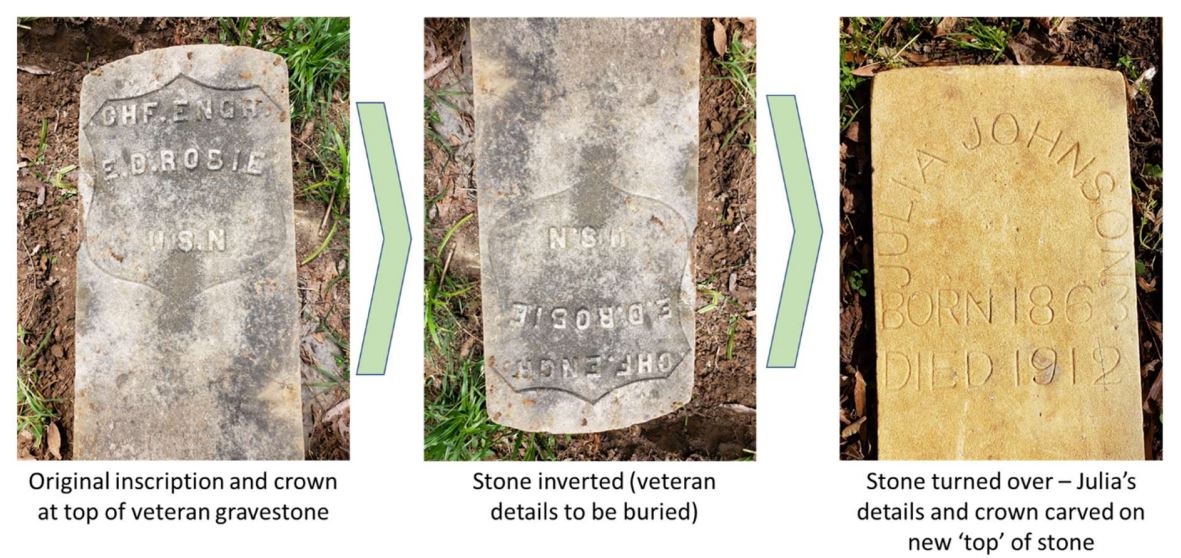

Depiction of how Gravestones could be reused economically | Source: Patrick Tisdale, "Acquiring Higher Quality Yet Affordable Gravestones."

Many of the gravestones at Mount Zion and the Female Union Band Society Cemeteries reflect the resourcefulness of Black families who had limited access to wealth or formal burial services. To honor their loved ones with dignity, families often used alternative materials such as discarded military gravestones or marble slabs made for furniture. These options were more affordable than commissioning new stones and offered a stronger and longer lasting choice than wood or concrete markers.

Repurposed military gravestones were sometimes flipped and inscribed on the blank side, with the original name buried underground. Marble slabs from dressers and vanities were known to be used, sometimes painted or fitted with a plaque instead of carved, due to how thin the stone was. These creative solutions reflect not only the financial realities of the surrounding community but also their deep commitment to memorialization as a cultural practice, using what was available to preserve memory and dignity.

About the Cemetery Vault

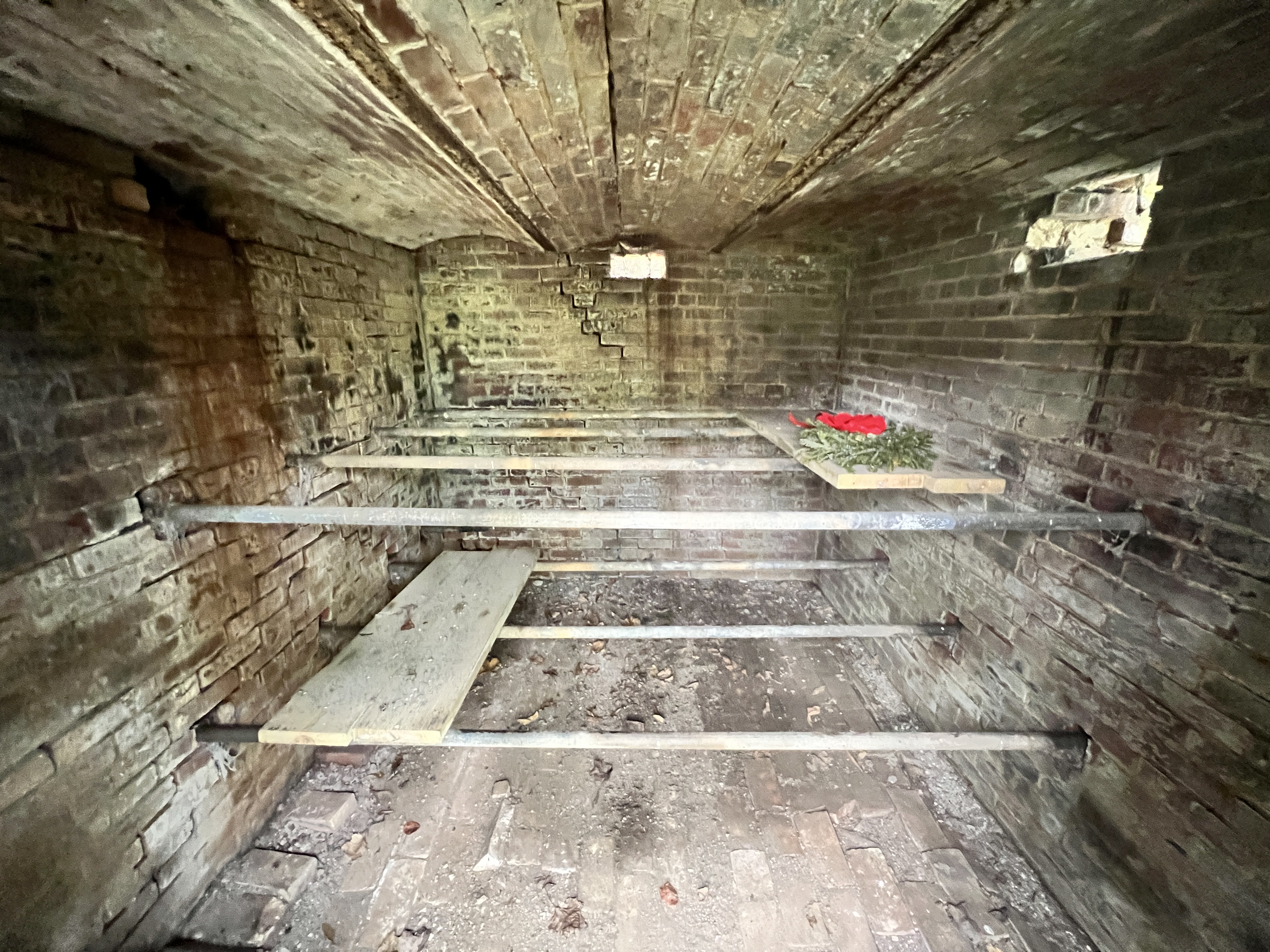

Mount Zion Cemetery vault, believed to have been used as an Underground Railroad shelter. | Source: Atlas Obscura.

The vault at Mount Zion and Female Union Band Society Cemeteries is one of the most recognized landmarks on the grounds. Built in the early 1800s by the Presbyterian church, it was first used as a holding tomb during winter months when the ground was too cold to bury the dead. As the cemetery became part of the Black community’s sacred space, the vault took on new layers of meaning. The vault also served a dual purpose for its community and African-Americans as a whole as a stop on the underground railroad. Through the undocumented and secretive oral tradition that fueled the railroad’s mission, the vault was believed to be a waypoint for enslaved persons who were traveling north along Rock Creek to Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania was considered an extremely desirable destination for former enslaved peoples due to its indifference towards enforcing immoral laws such as the Fugitive Slave Act and its expansion of personal liberty laws which further weakened attempts to capture former slaves.

Inside the vault. Built into the hillside, this space once served both sacred and practical needs, offering protection to the living travelling through Rock Creek Park and a transition space for the recently departed.

Today, the vault stands not just as a remnant of the past, but as a symbol of Black resilience, memory, and ongoing care for these grounds.

The Story of Nannie

Gravestone of Nannie, a 7-year-old girl who died in 1856, located at Mount Zion and Female Union Band Society Cemeteries. Photo by Kayla Benjamin, courtesy of The Washington Informer.

Though little is known about her life, Nannie’s grave has become a notable and powerful site at the cemeteries. Her gravestone, carved with her name and the dates of her short life (May 26, 1848 - May 18, 1856) is one of the most interacted with graves in the cemeteries. Local historians believe, based on corroborating official registers, her true name may have been Francis Tinny, with the possibility of “Nannie” being a rhyming nickname to “Frannie.” What remains unknown about her is part of what makes her grave so meaningful to visitors: she stands in for the many children buried in the cemeteries whose lives were cut short and whose memories are still lost to us.

Her story stepped into the spotlight on the weekend following the first federally recognized Juneteenth holiday 2023, when someone intentionally set fire to objects around her gravestone. In the aftermath, community members rallied around her to bring new offerings and support the Black Georgetown Foundation’s mission.

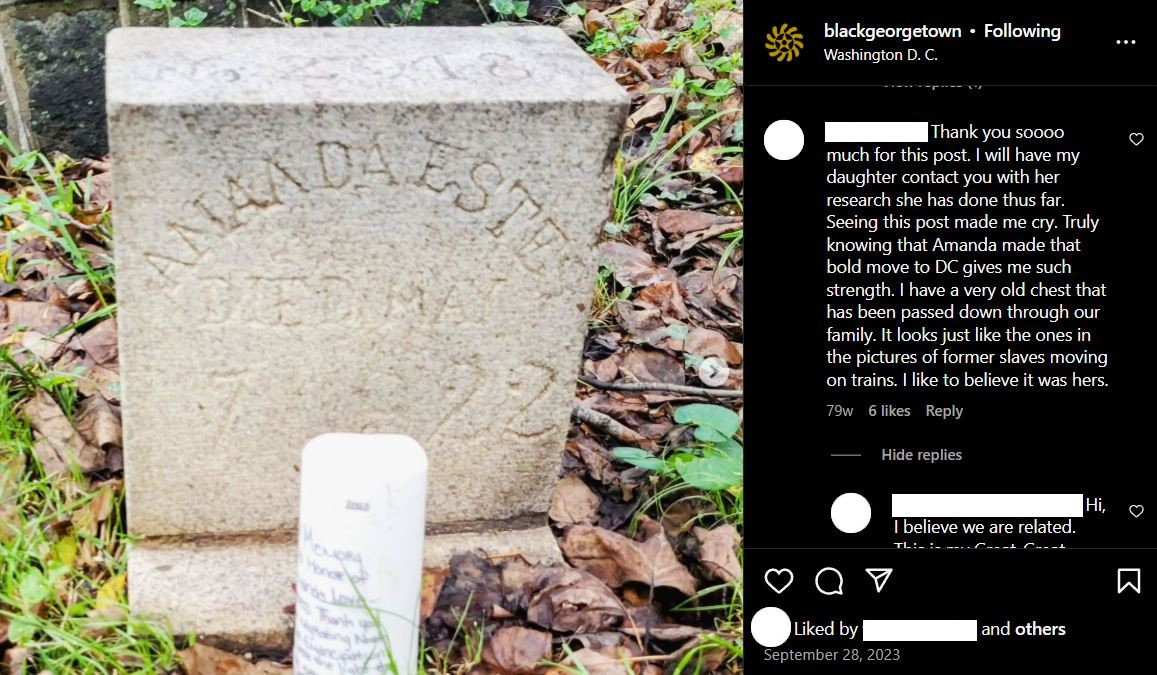

Amanda Love Estes

Amanda Love Estes, as pictured in a tintype-style portrait. | Source: Cemeteries Information System, Mount Zion–Female Union Band Society Historic Memorial Park.

Amanda Love Estes was born into slavery around May 1850 in the shadow of Crowders Mountain, a rocky peak rising from the piedmont landscape of Gaston County in North Carolina. At the age of 14, her name appears on an 1863 valuation list where she was priced as human property at $1,137. Following Emancipation, she migrated north and settled in the Georgetown area of Washington D.C., where she built a life for herself. At 1918 M Street NW, she raised eight children with her husband Thomas Odell Estes while working as a housekeeper and remaining deeply connected to community life through her membership at Mount Zion Methodist Church. Amanda died at home on May 7, 1922, at the age of 72. Her funeral was handled by George W. Wise, and she was laid to rest in the Female Union Band Society Cemetery near the Logan family plot.

In 2023, a note appeared at her gravestone, written with permanent marker on a white plastic candle.

In Memory and Honor of Amanda Love Estes. Thank you for migrating North after Emancipation. You were the light that lit the way.

Love your great, great, 3x Granddaughter

When the Black Georgetown Foundation shared this story online through an Instagram post, the comment section became a node of communal memory. Others responded: one descendant identified Amanda as her great-great-grandmother, directed to her through a DNA test. These exchanges display how the memory work being conducted by the Black Georgetown Foundation extends beyond the physical site and into our digital future. These small, intimate acts come together to form a collective thread of remembrance, where they reconnect descendants to their shared histories.

Instagram post featuring Amanda Estes's gravestone and candle | Source: Black Georgetown Foundation Instagram; @BlackGeorgetownFoundation

Dr. Collin B. Crusor

Dr. Colin Crusor, in a black and white portrait. | Source: Cemeteries Information System, Mount Zion–Female Union Band Society Historic Memorial Park.

Dr. Collin Barton Crusor Jr. (1856–1904) was a Howard University graduate and a trusted physician to the Black Georgetown community. He was also known for his care for many who now rest in the cemeteries. He practiced medicine from the 1880s until his death in 1904. His committment went beyond clinical care: he was a steady, familiar presence during moments of loss for many families who relied on him.

Crusor’s legacy is grounded in both service and connection. He belonged to multiple community organizations, including the Masons, the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, and the Young Men Protective League as well as being an active member at Ebenezer A.M.E Church. Though he died of tuberculosis at the age of 48, he lives on through the many relatives buried alongside him and through his descendants who still visit and volunteer at the cemeteries. His monument, damaged over time and once toppled, remains a powerful symbol of his life spent in service to others.

Clement Beckett

Portrait of Beckett. | Source: Cemeteries Information System, Mount Zion–Female Union Band Society Historic Memorial Park.

Clement Beckett was born into slavery in Maryland in 1809. He gained his freedom in his early twenties and moved to Washington, D.C. to build a life in Georgetown. There, he worked as a provisioning merchant and lived with his wife Mary and their children at 32 Beall Street (now O Street Northwest). He was a longtime member and class leader at Ebenezer Methodist Episcopal Church, highlighting how faith and community were central to his life. Over the decades, he became a respected elder in Black Georgetown, known for the role he played in shaping the social and spiritual fabric of his neighborhood.

His legacy is especially tied to the history of the Prince Hall Freemasonry in Washington. Beckett joined Social Lodge #7 in 1838 and became a founding member of the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of D.C. when it was established in 1848. He served as its first Grand Pursuviant and held several other leadership positions, including Senior Grand Warden. A few days after the founding of the lodge, he also helped establish Hiram Lodge #4 and served as its first Worshipful Master. At the time of his death in 1901, he was the last surviving member of the Lodge’s original founders. Although not confirmed, he is likely buried in the Female Union Band Society Cemetery, where his name is inscribed on a shared memorial with his daughter Margaret.

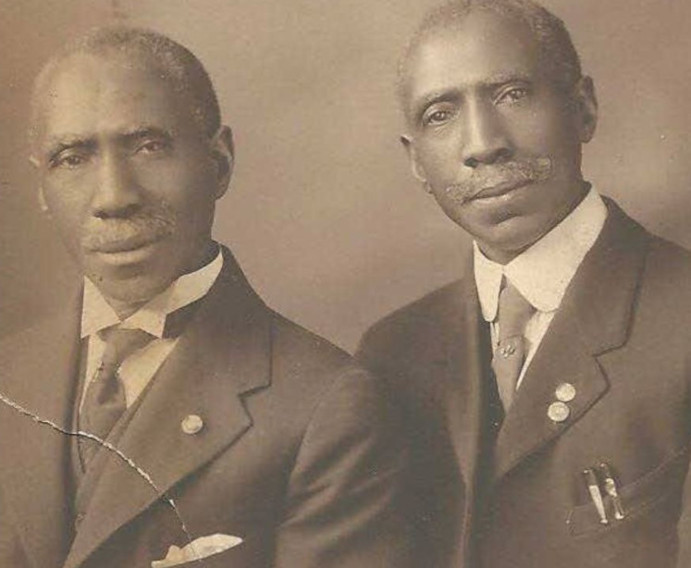

Charles Henry and James Lewis Turner

Charles Henry and James Lewis Turner, in a sepia-toned portrait. | Source: Cemeteries Information System, Mount Zion–Female Union Band Society Historic Memorial Park.

Charles Henry Turner was born into slavery along with his twin brother in 1856. They were emancipated on April 16, 1862 alongside their mother and grandmother through District of Columbia’s Compensated Emancipation Act. Their father, Hezekiah Turner, was a free man. Their enslaver, Mary Darne, received $96.50 in compensation for each child paid by the federal government. The Turner family’s story is a part of a larger history of Black life in Washington, D.C. where emanicpation came with both liberation and a stark reminder of the systems that commodified the existence of Black people.

Charles went on to become a dedicated member of the Georgetown community. He worshipped at Mount Zion Methodist Episcopal Church and served on its executive committee for Emancipation Day celebrations in 1896 and 1901 where he helped to publicly honor the freedom he gained as a child. When he died in 1939, at the age of 82, he was buried at the Female Union Band Society Cemetery with his parents beneath a shared gravestone that stands to this day. His life and legacy reflect both the trauma of enslavement and the resilience of a family that endured it and went on to contribute to their community for generations.

James Lewis Turner was born enslaved on July 31, 1856 alongside his twin brother Charles. Like him, he was emanicpated on April 16, 1862 at the age of five along with other members of his family. Darne’s compensation for James was listed at $98.55. After gaining his freedom, James built a life deeply rooted in Georgetown just like his brother - living, working, and raising a family there as well as helping to shape civic life. He worked as a reporter for the Washington Bee and was active in a wide range of community organizations such as the Emanicpation Club, Georgetown Republican Club, and multiple mutual aid socieities. Like his brother, he was a regular member of the Mount Zion Methodist Church. He was also involved in the West Washington Musical and Literary Association, alongside peers like Dr. Collin B. Crusor. He died on January 6, 1920 at the age of 63, almost two decades before his twin would pass. He was buried at Mount Zion with his wife, Mary E. Turner. Their gravestone, marked with the titles of “Father” and “Mother” reflects their devotion to family and a legacy of service grounded in a community that once witnessed their enslavement.

Benjamin Franklin Jennings

Benjamin Franklin Jennings, standing outside a home. | Source: Cemeteries Information System, Mount Zion–Female Union Band Society Historic Memorial Park.

Benjamin Franklin Jennings was born into slavery on March 4, 1836, in Montpelier Station, Virginia. His father was Paul Jennings, an enslaved person who had served in the White House. His mother was Fanny Gordon, who was enslaved nearby. Franklin was possibly paternally related to Benjamin Jennings, a white English trader, though they had no relationship beyond name. In may of 1864, Franklin fled bondage and enlisted in the 5th Regiment Massachusetts Colored Cavalry. The regiment fought dismounted in major campaigns including Petersburg and the occupation of Richmond, where they helped to challenge postwar racial control by resisting pass laws targeting Black residents. His regiment would ultimately lose 123, 116 of them to disease and 7 to combat.

After the war, he married Mary Logan in the District of Columbia and settled in Dumfries, Virginia. There he raised four children and maintaned a life rooting in farming and faith. He remained active in veterans’ gatherings and in 1896 filed a legal suit on behalf of his sister Frances, whose family home had been taken by a caregiver after she was committed to an asylum. Jennings died in 1926, at the age of 90, at the home of son Hugh in Kopp, Virginia. His memorial services were held at 2125 K Street in Washington, D.C. before finally being laid to rest at the Female Union Society Cemetery in Georgetown.

Jennings, second from right, posing for a photo at a veterans reunion for colored troops (nd) | Source: Cemeteries Information System, Mount Zion–Female Union Band Society Historic Memorial Park.

Franklin is interred beside his wife Mary. Their shared memorial remembers her as a devoted wife and mother, while his notes his service to the union during the civil war. Jennings’ service placed him at the center of both the struggle to end slavery but also the vision that would be crafted for society afterwards.

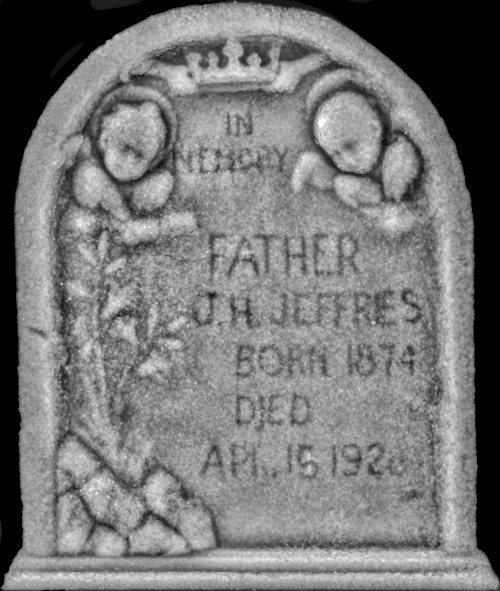

James H. “J. H.” Jeffries

Gravestone of James "J. H." Jeffries. | Source: Cemeteries Information System, Mount Zion–Female Union Band Society Historic Memorial Park.

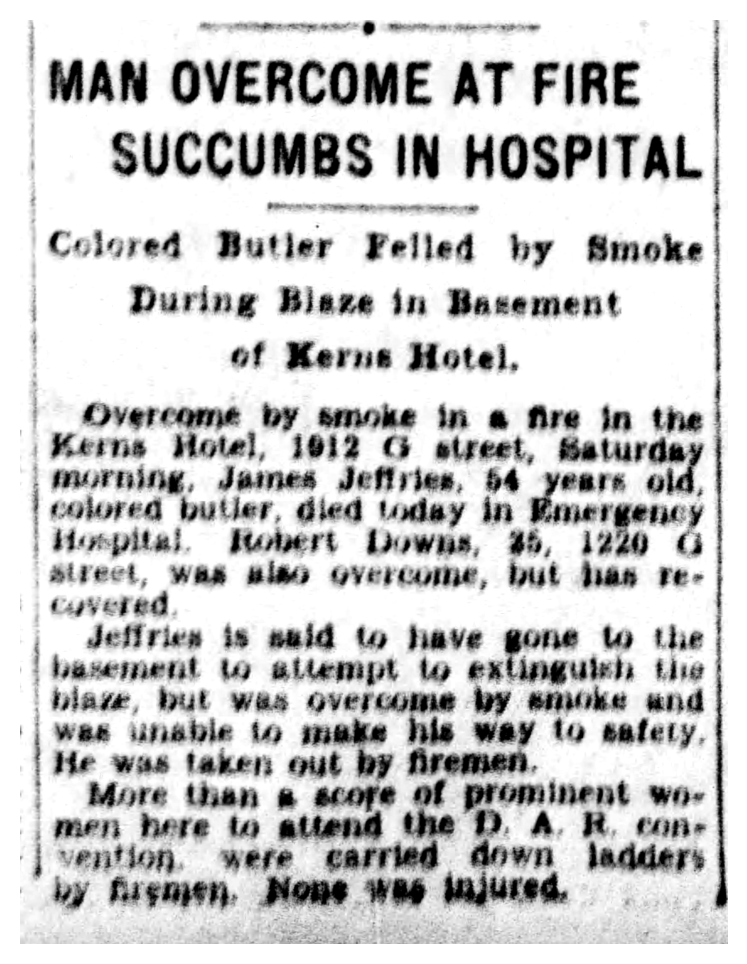

James H. “J. H.” Jeffries was born in Washington, D.C., likely in October 1871. He lived most of his life in the Georgetown area. During his life, he worked as a butler at the Kerns Hotel on G Street, which was a position he held with dedication until his tragic death in 1928. On April 16th, 1928, a fire broke out in basement of the Kerns Hotel. Jeffries made his way to the basement and attempted to put out the fire himself, but was sadly overcome along with another employee named Robert Downs. Jeffries was rescued by firemen responding to the scene. While Downs would survive the fire, Jeffries would succumb to his smoke inhalation later that day the Emergency Hospital. His death notice was published the same day in the The Evening Star.

Article published in the April 16, 1928 issue of The Evening Star; Enhanced with contrast for readability | Source: Cemeteries Information System, Mount Zion–Female Union Band Society Historic Memorial Park.

Before his passing, Jeffries lived at 2619 O Street Northwest with his wife Annie, whom he married in 1895. He was a member of the Mount Zion Methodist Episcopal (M.E) Church and may have been the father of James L. Jeffries Jr. and Edward E. Jeffries, both of whom died relatively young. His brother Ernest, was also part of his household. Jeffries is buried at Mount Zion Cemetery, where his monument simply reads: “Father.” His story speaks to the everyday labor, risk, and dignity that defined so many lives laid to rest at the cemeteries. As a butler, his life was likely shaped by the service he provided to others, while his death on the job underscores the vulnerability of working-class Black Washingtonians in the early 20th century, who often labored in physically demanding and hazardous roles without protections.

His life is a reminder that the people interred at the two cemeteries are not only well-known or celebrated community figures, but normal people - fathers, mothers, daughters, sons - whose lives were shaped by their labor, faith, struggle, and love for each other. Their small acts of bravery, like Jeffries risking his safety for the benefit of others, highlights their dedication to every aspect of their community. The cemeteries hold the stories of those who built and sustained Black Georgetown, often behind the scenes, and whose dignity in life is preserved through remembrance in death.

The wholeness of a people is diminished if the ancestors are not honored.

- Vincent deForest, 2021